What’s in a name? From Madame Geneva to mother’s ruin.

As we’ve been sharing the joys of Mothers Ruined Gin at festivals and tastings, we’ve been surprised to discover how many people have never heard the term ‘mother’s ruin’. As English lasses, this term for gin is part of our history and folklore, linked to the British ‘gin craze’ of the 1700s. With many of our customers being curious about our company name as well as showing a lively interest in the history of gin, we’ve invited historian and gin fan Dr Amanda McVitty to tell us more about the long and colourful history of women and gin. Pour yourself a glass and settle in for a fascinating read!

Amanda is an award-winning professional historian and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. She is the founder of Arque Research (www.arqueresearch.com), a specialist research and heritage marketing consultancy. A medievalist by training, Amanda’s specialities include the history of gender and sexuality, women’s history and urban history. Reach her at contact@arqueresearch.com.

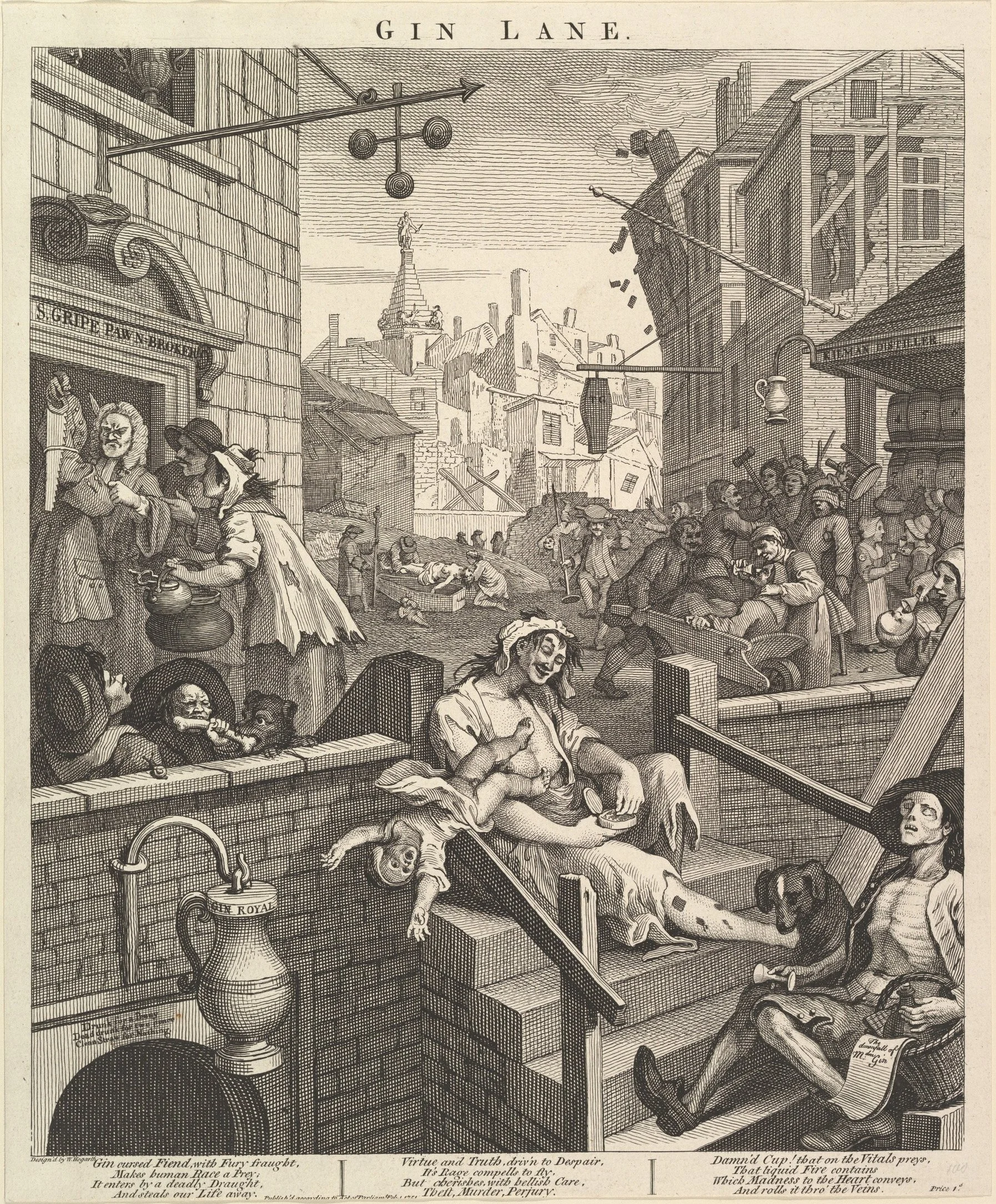

Gin Lane

In 1751, the artist and social critic William Hogarth released what would become perhaps his most famous work, the chaotic streetscape of Gin Lane. The etching speaks volumes about the moral panic that gripped English society at the height of the so-called ‘gin craze’. Amidst crumbling buildings and debauched women, the pub sign at bottom left offers, ‘Drunk for a Penny. Dead drunk for two pence. Clean Straw for Nothing’. Nearby, a skeletal figure clutches a bottle and a pamphlet warning of ‘The downfall of Madam Gin’, while a punning shop sign advertises ‘Kilman Distiller’.

Gin, ‘the bewytching liquor’, had only recently arrived in Britain with William of Orange and the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688. This had seen the Catholic king, James II, deposed and driven into exile and his throne offered to the staunchly Protestant William, Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. William was married to James’ eldest daughter Mary and they took the thrones of England and Scotland as William III and Mary II. (For fans of the series Outlander, these are the events that eventually lead to the botched attempts to restore ‘James III’ and the calamitous battle of Culloden.)

Gin had long been the Dutch national drink and William III adored it (some said rather too much at times!). His new subjects quickly adopted it as their drink of choice, too, a symbol of patriotism and Protestantism. Gin’s popularity then soared when England and their Dutch allies went to war with Catholic France, and imports of French wine and brandy – of which vast quantities were consumed – were banned.

Liberating the skills of women distillers

A momentous shift occurred in 1690 when the monopoly of the male-run London Distillers Guild was broken with a new ‘Act for encouraging the distilling of brandy and spirits from corn’. This opened up the gin trade to anyone with the means and resources, which could be as minimal as a small homemade still (something the size of Mothers Ruined’s original ‘Patsy’).

Given this opportunity, women took their long experience of small-scale domestic distilling and ran with it. Using female skills and knowledge that had been passed down since medieval times of how to make alcohol-based medicines and therapeutic tonics, they turned to making gin for fun and profit.

By the early 1700s, gin was being downed everywhere from the palaces and private clubs of the aristocracy to hole-in-the-wall home ‘dram shops’, pubs, and even from barrows wheeled through the streets. An official report from 1723 estimated that every man, woman and child in London was downing an extraordinary half-litre of gin a week!

Women, gin and sin

But there were growing concerns that women were falling into sin and depravity through making and drinking gin. As one commentator put it, ‘suddenly women were reeling drunkenly out of chandler’s shops, and selling drams on street corners’.[i] Stories abounded of women selling their clothing, bodies, and even their children to buy gin. Hawking gin and selling one’s body were seen as synonymous, and for poor women, gin distilling and prostitution were indeed often complementary ways to make enough money to keep body, if not soul, together.

The gendered names and iconography of gin – so graphically captured in Hogarth’s Gin Lane – came to personify the mortal peril gin represented to women’s bodies and souls: Madame Geneva, Mother Gin and, of course, mother’s ruin.

Debates on the gin trade raged in the popular press, with famous authors like Samuel Johnson and Daniel Defoe writing for and against, as well as through ballads. These were the ‘top 40’ hits of the time, performed in pubs, on street corners and at that always-popular form of premodern entertainment, the public execution.

But those are tales for another day, and we’ll pick them up in our next blog on the history of gin. And perhaps we’ll even sing a few gin ditties at our upcoming ‘History and Gin’ events – watch this space!

1 Patrick Dillon, Gin: The Much Lamented Death of Madame Geneva (2003).